Brush up on your vocal anatomy by learning what the posterior cricoarytenoid is and its role in singing.

Vocal anatomy can be a minefield, especially when a lot of the terminology sounds more like pasta dishes, Harry Potter spells or Jurassic creatures than body parts. Consider the longus capitis, levatores costarum and the pterygoids, and tell me I’m wrong.

Let’s make sense of one particular part of vocal anatomy: the posterior cricoarytenoid (PCA).

What is the PCA?

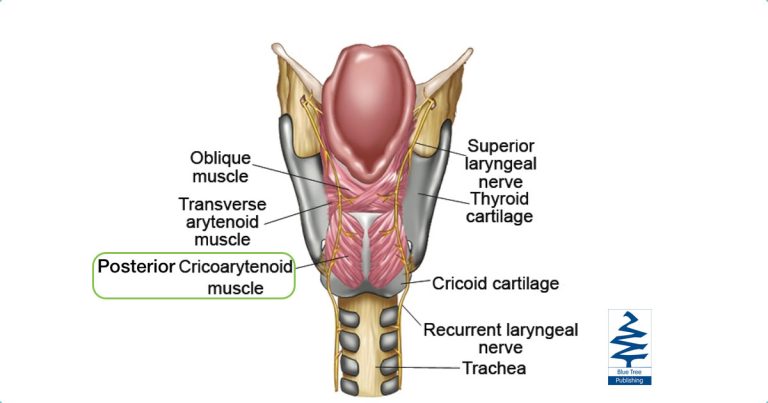

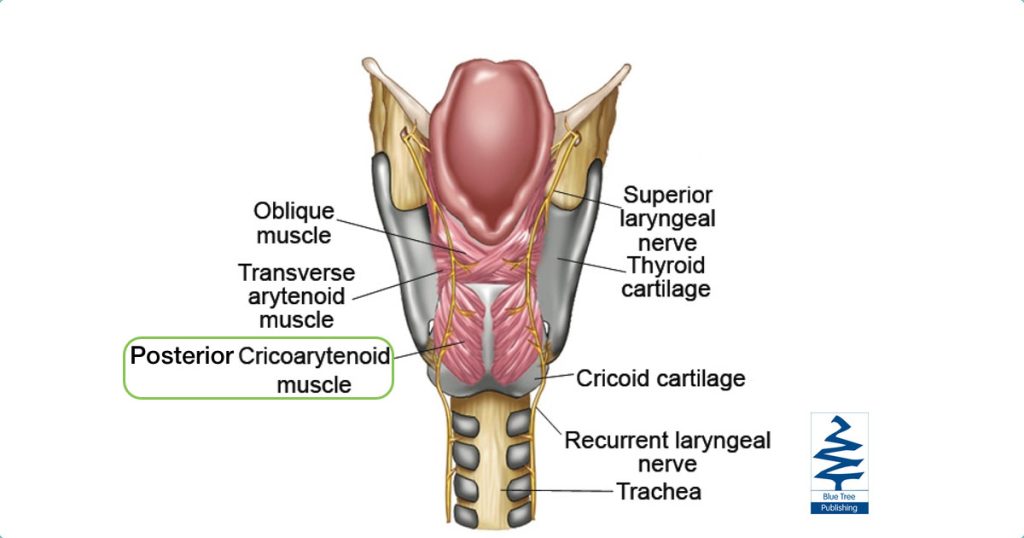

The PCA is an intrinsic laryngeal muscle and looks like a flapper’s feather fan (there’s a nice bit of alliteration for you!).

Let’s break that down:

Posterior: This means towards the back of the body or structure.

Cricoarytenoid: Has attachments to both the cricoid cartilage and arytenoid cartilage.

Intrinsic: Inside the larynx.

What is the function of the PCA?

The PCA is an abductor, which means it opens the vocal folds for air to flow freely through the glottis.

Remember, when we talk about vocal anatomy, abduct means to take away. Conversely, Adduct means to add to; to close.

In Anatomy of Voice, Calais-Germain and Germain explain how “the cricoarytenoid pulls the muscular process medially, which rotates the arytenoid cartilage in a way that separates the vocal processes; this, in turn, spreads the posterior part of the vocal cords”. (2013).

Like the other intrinsic laryngeal muscles (with the exception of the cricothyroid), the PCA is innervated by the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Check out our blog The Laryngeal Nerves here!

While the PCA is an abductor, studies have been carried out to determine the activity of PCA during phonation.

“Although the PCA muscle may not play a primary role in phonation, it appears important for fine control of subglottic pressure, frequency and intensity.” (Hong-Shik Choi et al, 1993)

‘Anatomy guru’ Stephen King talks about the PCA in the Singing Teachers Talk podcast.

Stephen says: “If the engagement of the PCA opens the glottis, but literally all of the other muscles are designed to close it, that means that we can have the PCA engaged and some other things engaged which might stabilise phonation.

“So if the adductors are working, but then we don’t want so much squeeze, we need to engage the PCA, maybe, to create a resultant force that enables the opposite. It’s not necessarily about just disengaging TA (the thyroarytenoid muscle).”

Learn more about the PCA by listening to the full interview with Stephen here.

References

Anatomy of Voice by Blandine Calais-Germain & Francios Germain

The Laryngeal Nerves, BAST Blog

Function of the Posterior Cricoarytenoid Muscle in Phonation: In Vivo Laryngeal Model by Hong-Shik Choi et all; 1993.